Government wants public service wage bill curtailed as unions threaten indefinite strike

The failure of government and organised labour to resolve the current impasse on the ongoing salary negotiations has caused uncertainty and sparked fears in the country, particularly as unions threaten to down tools.

Providing frontline services

Firstly, the unions involved in the dispute represent employees who provide basic frontline activities, and the withdrawal of their labour would disrupt vital services ranging from border control and policing to health to revenue collection, among others.

Secondly, economists warn that the country cannot afford another strike action after the recent Transnet one, which nearly crippled the country’s logistics. This was in addition to other recent calamities such the social unrest in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) and Gauteng as well as the devastating floods that hit KZN and some parts of the Eastern Cape.

Deterioration of GDP growth

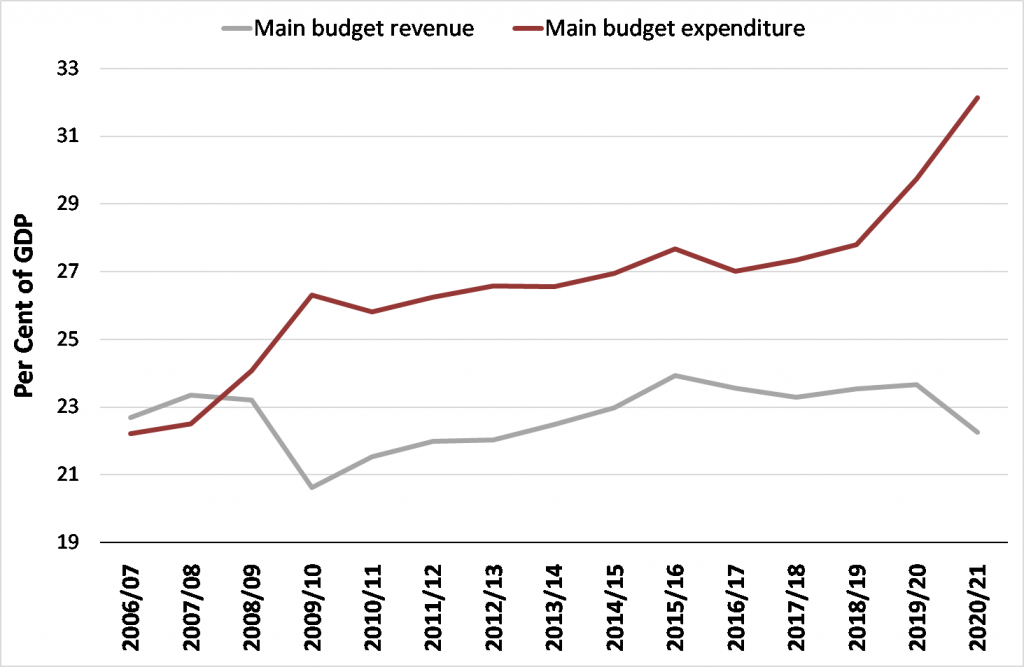

The unions accuse government of negotiating in bad faith and undermining labour bargaining processes. Similarly, government laments labour’s lack of appreciation of the magnitude of the fiscal challenges it faces, chief of which is deterioration in GDP growth. “The higher than expected global inflation could also lead to higher global interest rates, affecting debt service costs and the exchange rate,” said government, adding, “the public sector wage bill is under severe pressure due to the general constraints faced by the South African economy.”

Disrupting fiscal outlook

Furthermore, government pointed out that the public sector “wage bill has grown faster than economic growth over many years” and that it cannot afford the level of wage hikes the public service unions are demanding. It said this would dramatically disrupt the fiscal outlook, thereby compromising government’s efforts to deliver public services.

“Such high-cost demands would further frustrate the government’s efforts to continue working on a sustainable long term approach to social protection consistent with government’s broad development mandate and the need to ensure affordability,” said the government.

Q&A for DPSA

The Mail & Guardian sent 10 questions to the department of Public Service and Administration (DPSA)’s chief negotiator, Mompati Galorale, to provide perspective and context of government’s position related to the protracted salary negotiations.

Can you please give us a brief background of when salary negotiations between government and organised labour started?

Negotiations commenced in April 2022 with a pre-negotiations session, in which government presented the country’s economic outlook, fiscal framework and planning cycle.

The re-alignment of the negotiations relate to the government’s planning cycle. To this effect a timetable to guide the process was agreed upon. Negotiations for the financial year 2022/23 should have concluded at the end June 2022 so that the outcomes thereof could be incorporated into the October 2022 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS). This would have also allowed the negotiations for the financial year 2023/24 to commence immediately, such that the outcomes thereof could be incorporated into the 2023/24 final budget.

During the pre-negotiations process, government indicated that the gap between revenue and expenditure continues to widen, with expenditure growing faster than revenue. Debt-service-costs also continue to rise, crowding out spending on essential public services and as a result, public spending is on an unsustainable path.

In your view, what led to the current impasse between the parties involved?

The party positions were too far apart to begin with. Government derives revenue from taxes and the tax base has been seriously eroded by the sluggish and shrinking economy, worsened by the Covid-19 pandemic. The total cost of the labour demands is R147 billion, with the 10% cost-of-living adjustment demand alone needing R50 billion.

The employer indicated that an amount of R147 billion, which is the total cost of labour’s demands, is not affordable and would disrupt the fiscal policy, thereby compromising the government’s efforts to deliver services.

Such high-cost demands would further frustrate the government’s efforts to continue working on a sustainable long-term approach to social protection consistent with its broad development mandate and the need to ensure affordability.

It was because of the above factors that the employer proposed that the employees continue to be paid a non-pensionable cash allowance, which is an average of 4.5% of the 20 billion allocated in the 2022/23 compensation budget, plus a 3% pensionable increase for the 2022/23 financial year, which equates to a 7.5% adjustment.

Organised labour accuses you of reneging on the three-year wage deal you made in 2018, thereby compromising the integrity of collective bargaining; what is your response?

It was the Public Servants Association (PSA) that hurried out of the engagements at the Public Service Co-ordinating Bargaining Council (PSCBC), where the employer tabled a request for a review and took the matter to the labour court. It became apparent that the government would not sustain two parallel processes, one in the labour court, and another in the bargaining council. After the PSA took the matter to court, government as a respondent was then forced to file its papers in response to the PSA’s application.

Related to the above, labour also claims that it is unconscionable for DPSA to refuse their salary increase while President Cyril Ramaphosa has recently accepted recommendations of the Independent Commission for the Remuneration of Public Office-Bearers to increase politician’s salaries by 3%. What is your take on this?

The current offer far surpasses what public office bearers received, in that the offer is made of two components, which are the 4.5% non-pensionable cash allowance and a 3% pensionable increase, constituting on average a 7.5% increase in salaries. In addition to this increase, there is also a 1.5% pay progression for qualifying employees, meaning for many public servants the total adjustment for this year could be 9% (3%+1.5%=4.5% pensionable increase plus 4.5% non-pensionable cash allowance).

Government has unilaterally forged ahead and tabled a final offer of 7.5%; doesn’t this lend credence to labour’s accusation that you ride roughshod over the principles of collective bargaining?

No. Having considered the risks of public servants not receiving any salary increase for the 2022/23 financial year, if no agreement was reached on time before the minister of finance tabled the 2022 MTBPS, government took a decision in the interest of the public servants to implement its final offer.

Can you please break down or explain what your revised offer entails?

There is no revised offer. The final offer remains as explained above.

DPSA stressed the need for organised labour to align salary negotiations with treasury’s budgeting process; why is this necessary?

It is necessary for purposes of incorporating the outcomes of negotiations into the final budget. This will avoid negotiating after the effect, when the budget has already been appropriated.

In real terms, how much would organised labour’s salary increase cost the national fiscus?

Their 10% demand would have cost the fiscus R50 billion for the financial year 2022/23. The 3% pensionable increase amounts to R13.4 billion, which is an additional amount to the R20.5 billion which was originally in the budget to cover the 4.5% non-pensionable allowance for the 2022/23 financial year.

You claim to have shared with labour the country’s fragile economic situation, but labour did not share this perspective. Why do you think they insist on getting their demand met regardless?

Despite government having shared openly with labour the country’s fiscal position as outlined above, they still chose to stick to their demands.

Are you optimistic that the parties will finally reach a settlement, and why?

Government remains optimistic, hence the call for labour to come back to the table to commence negotiations for the 2023/24 financial year. — Thabo Mohlala